AI Policy: An African and Global Emergency (Opinion)

Since Edward Bernays, nephew to Sigmund Freud, applied his influential uncle’s work to branding and advertising, the field of propaganda has never been the same. You might not know who this man is; you might have never even heard his name – but you are aware of the term Public Relations. This phrase was coined by none other than Edward because when he wanted to brand his establishment that focused on swaying public opinion, propaganda sounded like a dirty word. A small change in vocabulary, right? Nothing that we need to pay close attention to. But by the turn of the century, Edward and his team of psychologists had figured out how to introduce women to smoking publicly, kick-started the notion of ready-made home meals with the formula pancake, got Americans excited about a war in the midst of the Great Depression, and most impressively, if you ask me – got the American public to like the rather bland passing head of state that was President Coolidge. This was done by organizing the first White House celebrity gathering, a practice that lives on to this day in American politics.

Today, propaganda has moved on from the newspapers and occasional appearances on television to live in our pockets, waiting for the moment when we open our phones. And unlike the propaganda of old, which had to cast a wide net to catch its fish, now we have data to pinpoint habits and behaviors. Tailor-made propaganda, just for you. Tales of influenced elections and outright warmongering by companies like Cambridge Analytica are now popular media legends, and even Netflix has a whole documentary on how users are influenced by social media “suggestions”. Still, we have not moved for stronger regulation because in all of this, one could argue that we are still dealing in the realm of disinformation and misinformation. We are yet to cross the line into the space of outright illusion. This is about to change. No, this has already changed.

First Celebrity Breakfast at the White House organized to improve public perception of President Coolidge.

If you are a millennial with any interest in rap music, perhaps you might have heard about the clash of modern legends in what some are calling the Battle of the Big 3. While I am a fan of the culture myself with Kendrick Lamar as my champion, the influence of AI in this ongoing “beef” has rattled me in ways I had not anticipated. To start with, when Drake dropped his record in response to the who-is-number-one in the Big 3 debate, everyone paused to wonder if it was really Drake or if it was an AI fake. Thankfully, the artist was quick to come forward and claim the song. Great. About two weeks later, we heard two responses from Kendrick Lamar, and again the first reaction was to speculate if they were AI fakes or real. We aren’t talking about basic speeches here. We are talking about intricate rap flows with voice inflections and complex rhyme schemes. I have been listening to Kendrick Lamar’s music for over a decade, and I could not tell if I was listening to him or a computer-generated version. After much speculation, the sound engineer responsible for this AI fake came forward to tell the world he was behind it.

Kendrick Lamar – Owl Hunting – Response To Drake’s Push Ups (Drop & Give Me 50 Diss) Loza Alexander Sample of AI assisted music featuring voice, tone, and inflection cloning

This is all fun and games with entertainment where the risk of impersonation can be countered by the real artist accepting or denying the content, but what happens when it becomes a political tool? What happens when perfect clones of an opponent’s voice are used to spark tribalist sentiments in an African election? When such recordings are forwarded in siloed WhatsApp groups through populations lacking the skills to even conduct proper research for authentication? And unlike old-school propaganda where specific skills like graphic design and copywriting were required, the simplicity of AI prompting and its ability to learn and refine hyper-charges just how dangerous this technology can be if not properly safeguarded against misuse.

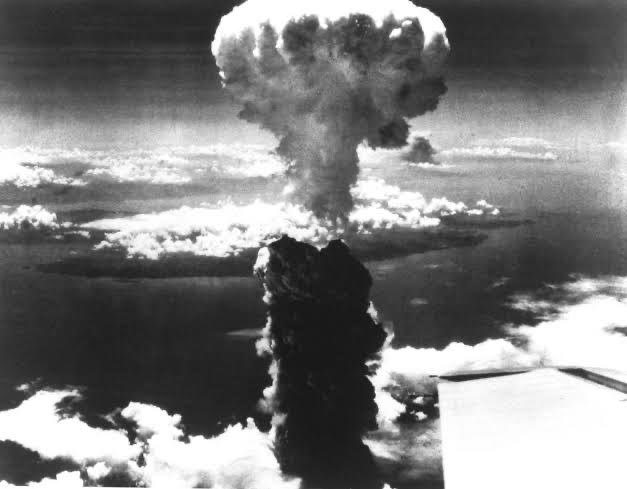

The detonation of the first atomic bomb in Hiroshima marking the beginning of the nuclear age and pushing the doomsday clock closest to midnight

It is understandable that the human psyche is prone to catastrophizing. It wouldn’t be the first time we thought technologies would end the world as we knew it, only for us to realize the biggest danger of the computer age is back problems from bad posture. A far cry from the predictions of the Matrix or the Terminator films where we ended up in complete machine tyranny. Thanks to the man versus machine trope popular in dystopian novels and the movies that followed, the average person is prone to thinking of the dangers of artificial intelligence as that of Us versus It. However, on closer inspection, like the atomic bomb and every other destructive form of technology that we have invented, the human behind the operation has always been the real threat.

To better understand the immediate dangers of this technology on the African continent, we must start framing it within the context of use in our culture and environment. Can you even begin to imagine the level of sophistication to expect from the proverbial African Prince when he gets his hand on AI with AGI? The political mudslinging we are soon to be witnessing when parties clash? With what is at stake, Africa cannot simply wait for the rest of the world to design a regulatory structure for us to follow. The time is now to start formulating what will constitute Africa’s position on AI-related technologies. Who is liable when AI errors result in deaths? How do we protect African artists from AI piracy? What are the regulatory tests required for models to pass to be deemed safe for the African population and its various ethnicities?

There are too many questions – but we cannot fall victim to analysis paralysis and do nothing. While the continent might have gotten away with the near copy and paste model mirroring foreign constitutions, AI will require a much more customized framework if it is to be effective in meeting our local needs. It has never been more important for stakeholders in Africa to begin to push for policy and regulation that prioritizes the well-being and flourishing of the African population in the near to distant future. It is with this need in mind that AfriLabs has made sure to dedicate a panel to the subject of AI and policies on the continent in this year’s AfriLabs Annual Gathering Conference. If perhaps you are a stakeholder in government, an activist with dread for an unregulated AI future, or an industry champion that sees the value in this conversation; your presence is very much welcome. If it takes a child to raise a village, it’s going to take a continent to raise AI.

AI generated image from Meta’s Llama 3.0 (Prompt: Black lawyer with robe and wig vs. AI robot in court)